Explore examples of my university assignments demonstrating research, analysis, and communication in action.

Academic Work

Research Essay

Introducing my essay, I Write, Therefore I Exist

Bringing Ancient Graffiti To Life

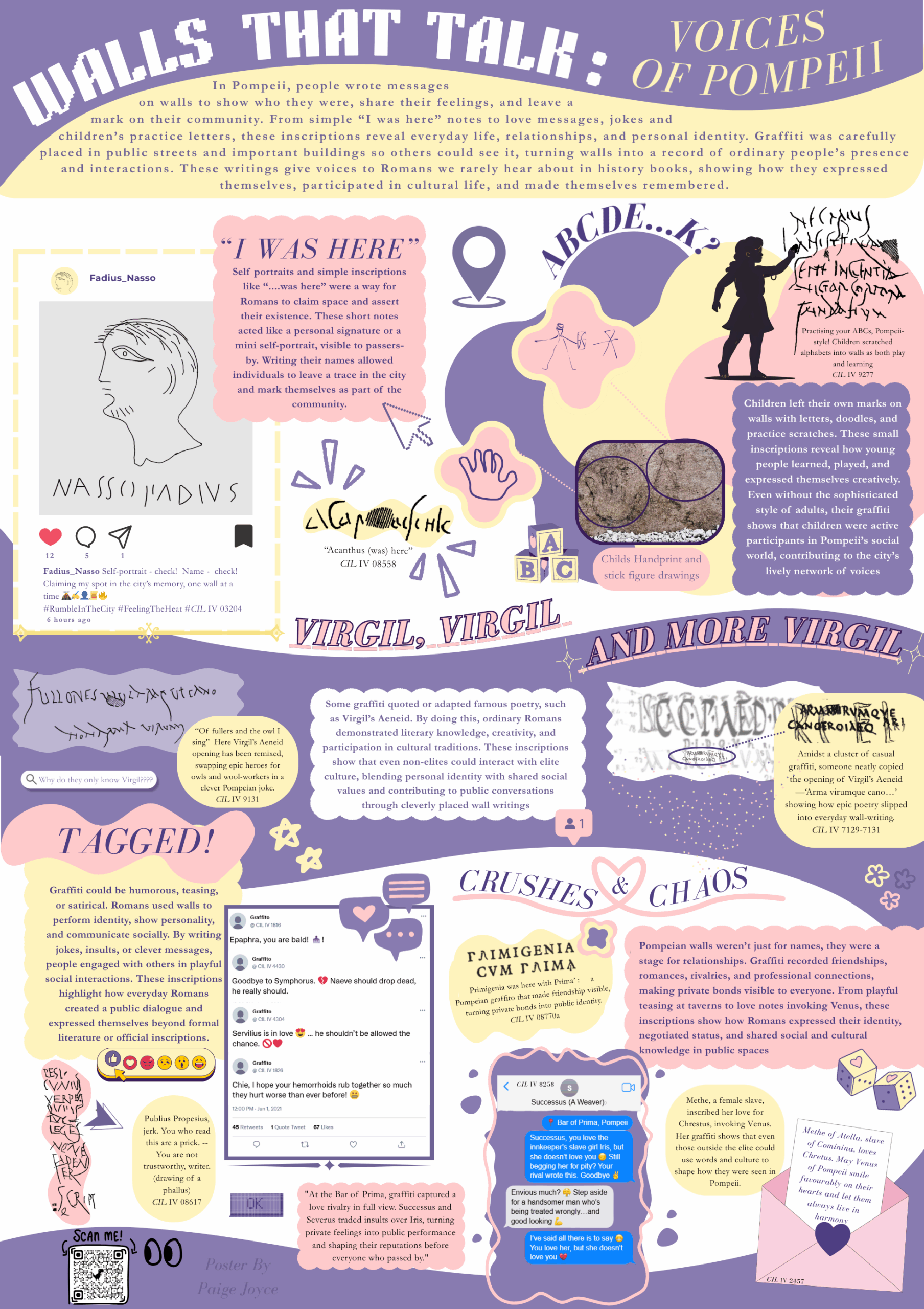

My poster invites students to explore how Romans expressed themselves, connected with others, and shared ideas

Source Analysis

The Olympeion Temple

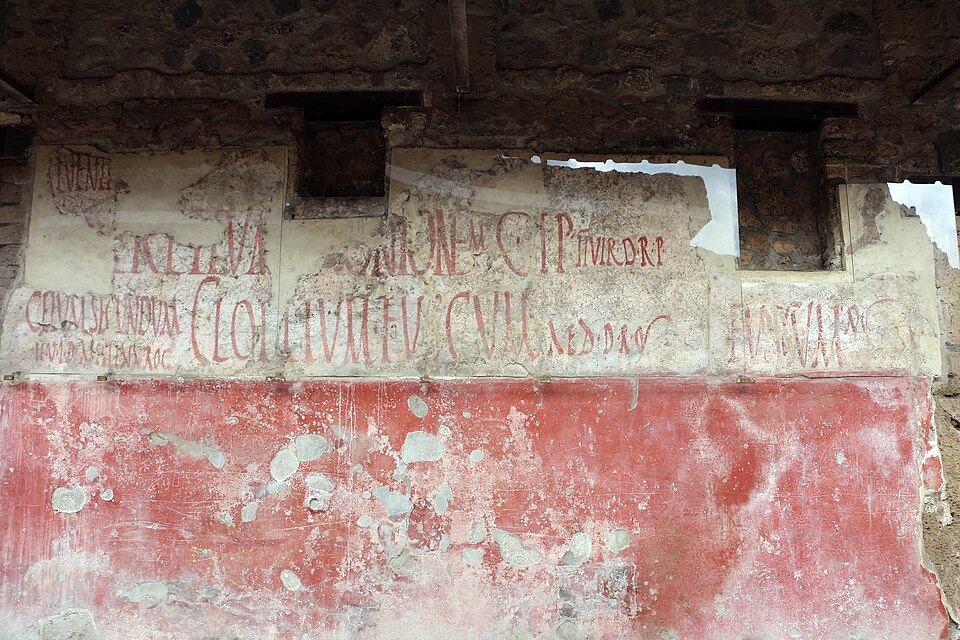

Graffiti in ancient Pompeii offers a remarkable insight into the lives, identities, and social interactions of ordinary Romans. My research essay, I Write, Therefore I Exist: Graffiti as a Medium of Communication and Identity Assertion, explores how graffiti functioned as a tool for self-expression, relational negotiation, and cultural participation. Drawing on examples from walls, public spaces, and domestic settings, the essay demonstrates that graffiti allowed individuals, including children, women, slaves, and soldiers, to assert their presence, communicate emotions, display literacy, and engage with shared cultural narratives. From simple inscriptions such as “Acanthus was here” to more complex adaptations of Virgilian poetry, Pompeian graffiti reveals a diverse, literate society that actively inscribed identity into public and semi-public spaces. These texts highlight both personal and social dimensions of communication, preserving voices that are largely absent from elite literary sources.

Bringing Ancient Graffiti to Life

My poster invites students to explore how Romans expressed themselves, connected with others, and shared ideas

The accompanying poster is designed for high school students aged 14–17 visiting a museum exhibition. Its goal is to make ancient graffiti relatable and engaging by framing it as a form of “social media,” drawing parallels between modern communication, texting, posting, and joking online, and the ways Pompeians left messages, jokes, love notes, and drawings on walls. The poster conveys that graffiti was more than random scribbles: it was a medium through which ordinary people expressed themselves, connected with others, and participated in cultural life. By using lively examples, humour, and familiar comparisons, the poster invites students to see ancient Romans as real, relatable people, fostering an understanding of how communication, identity, and social interaction have enduring significance across time.

source Analysis

The Olympeion

The Olympeion Temple (The Temple of Olympian Zeus), is a monumental ruin in central Athens dedicated to Zeus, begun in the 6th century BC and completed under Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD.

Introduction

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, or Olympieion, in Athens stands as one of the most ambitious and symbolically charged monuments of the ancient world. Built over several centuries and completed under the Roman emperor Hadrian in 131 CE, the temple embodies the evolving relationship between Greek identity and external power. Through its monumental architecture and shifting political associations, the Olympieion reveals how religious spaces could express authority, cultural pride, and imperial ideology simultaneously.

Context

The Olympieion, located southeast of the Acropolis near the River Ilissos, stands on a site sacred to Zeus since antiquity, with Pausanias attributing the first sanctuary to the mythical Deukalion[1]. The first major phase, beginning around 515 BCE under the Peisistratid tyrants, saw the construction of a Doric temple, intended to rival the grandeur of the great sanctuaries at Samos and Ephesos. Construction was abandoned in 510 BCE following the fall of the tyrants.

For nearly 350 years the site remained incomplete but continued to host the cult of Zeus Olympios. Heracleides described it as “half-finished but astonishing,” reflecting its enduring significance[2]. In the 2nd century BCE, Antiochos IV Epiphanes revived the project, employing the Roman architect Cossutius to rebuild it in the Corinthian order with Pentelic marble, though work ceased at his death in 164 BCE. Finally, between 124 and 132 CE, Hadrian completed the temple, added a peribolos wall, and constructed Hadrian’s Arch to mark the entrance to the renewed sanctuary.

Historical Significance and Interpretation.

The Olympeion is not merely a monumental temple but a prism through which the shifting dynamics of political power, cultural identity, and architectural ambition in Athens and the wider Mediterranean can be read. Its six-century-long construction history reveals that the temple was both a sacred site and a stage for rulers to project authority and prestige. Initially, under the Peisistratids, Aristotle’s remark that the tyrants undertook the project to keep citizens “poor and busy” highlights how monumental building could function as both a tool of social control and a visible symbol of despotic power[3].

The subsequent Hellenistic revival under Antiochos IV, praised by Polybios for its “surpassing generosity,” reinterpreted the site as a display of cosmopolitan magnificence, demonstrating the shift from local political symbolism to transregional Hellenistic competition and innovation, particularly through the introduction of the Corinthian order[4].

Roman engagement further reframed the temple: Sulla’s removal of columns for Rome, noted by Pliny the Elder, exemplifies the literal and symbolic appropriation of Greek grandeur to consolidate imperial ideology, while Augustan ambitions to dedicate the temple to his genius illustrate the embedding of Roman authority within Athenian sacred space[5]. Finally, Hadrian’s completion signifies the delicate negotiation between imperial power and local cultural memory; by preserving ancient shrines yet asserting his own urban imprint, Hadrian transformed the temple into a monument of continuity and adaptation.

However, Pausanias’ omission of Hadrian’s gate from his description likely reflects an effort to preserve a vision of Athens rooted in its Greek heritage rather than its Roman redefinition, further underscore the Olympeion’s enduring capacity to absorb successive layers of meaning[6]. Ultimately, the temple’s significance lies in its persistent role as a canvas for political ambition, cultural dialogue, and the negotiation of memory across centuries.

Reflections on Working with Ancient Evidence

Analysing the Olympeion has deepened my understanding of how monumental architecture functions as both political and cultural evidence. Working with a structure that evolved over centuries encouraged me to consider how meaning can change with context. I also developed a greater appreciation for how physical evidence such as architectural style or scale, can communicate ideology as clearly as written sources. Engaging with the Olympieion challenged me to interpret material cultural critically rather than descriptively. I learned to ask what messages a monument conveys, who commissioned it, and how contemporary viewers might have experienced it. This process improved my analytical skillset, particularly in connecting tangible artefacts to abstract themes of identify and authority that define much of the ancient world.

Conclusion

The Olympieion of Athens stands as a monumental record of changing political and cultural identities. From its origins in the Archaic period to its completion under Hadrian, the temple reflects how religious architecture could serve as an instrument of power and a medium for negotiating identity. Its colossal form, hybrid design, and enduring presence encapsulate Athens’ transformation from independent polis to imperial ally, while preserving its reputation as the heart of Greek civilisation. Analysing this evidence has deepened my understanding of how the ancient world used material culture to articulate the intertwined forces of culture, power, and belief.

[1] Paus. 1.18.6

[2] Heracleides Criticus. Bios Ellados. 1

[3] Arist. Pol. 5.9.4

[4] Ath. 5.194a

[5] Plin. NH. 36.45

[6] Paus. 1.18.8